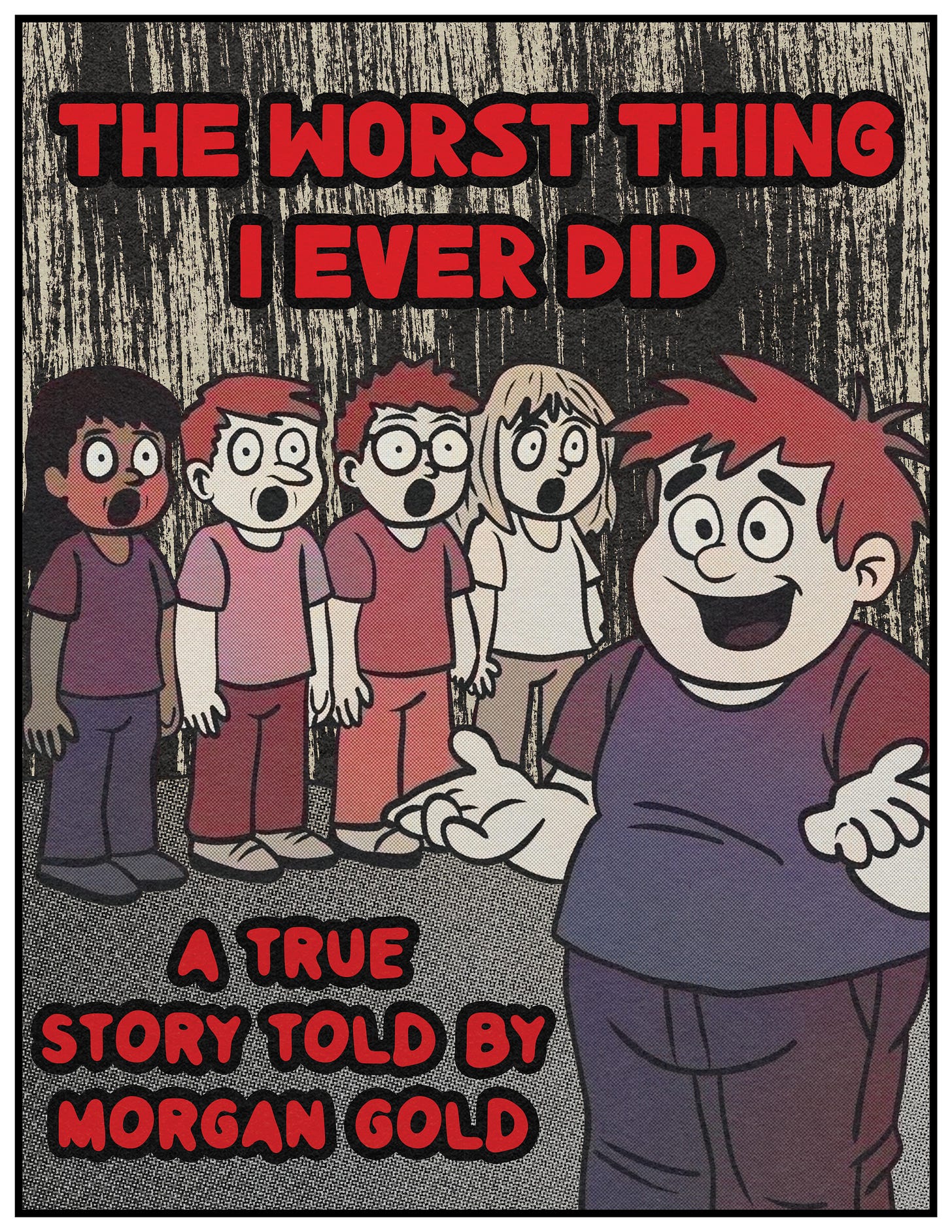

The Day I Became the Villain

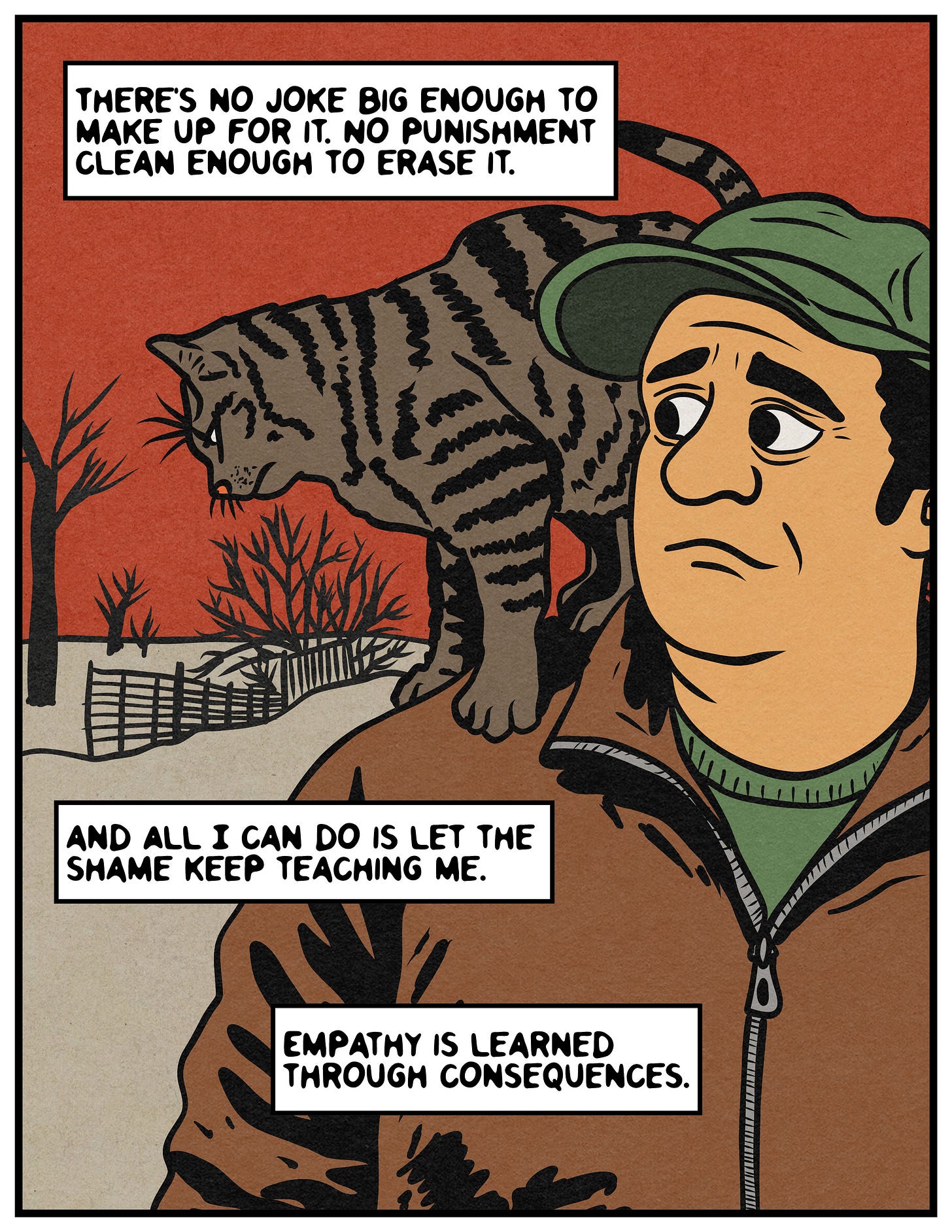

Empathy only comes from consequences: A guide to late regret, unintended harm, and not making it worse.

Should You Apologize Years Later?

I found her on Facebook.

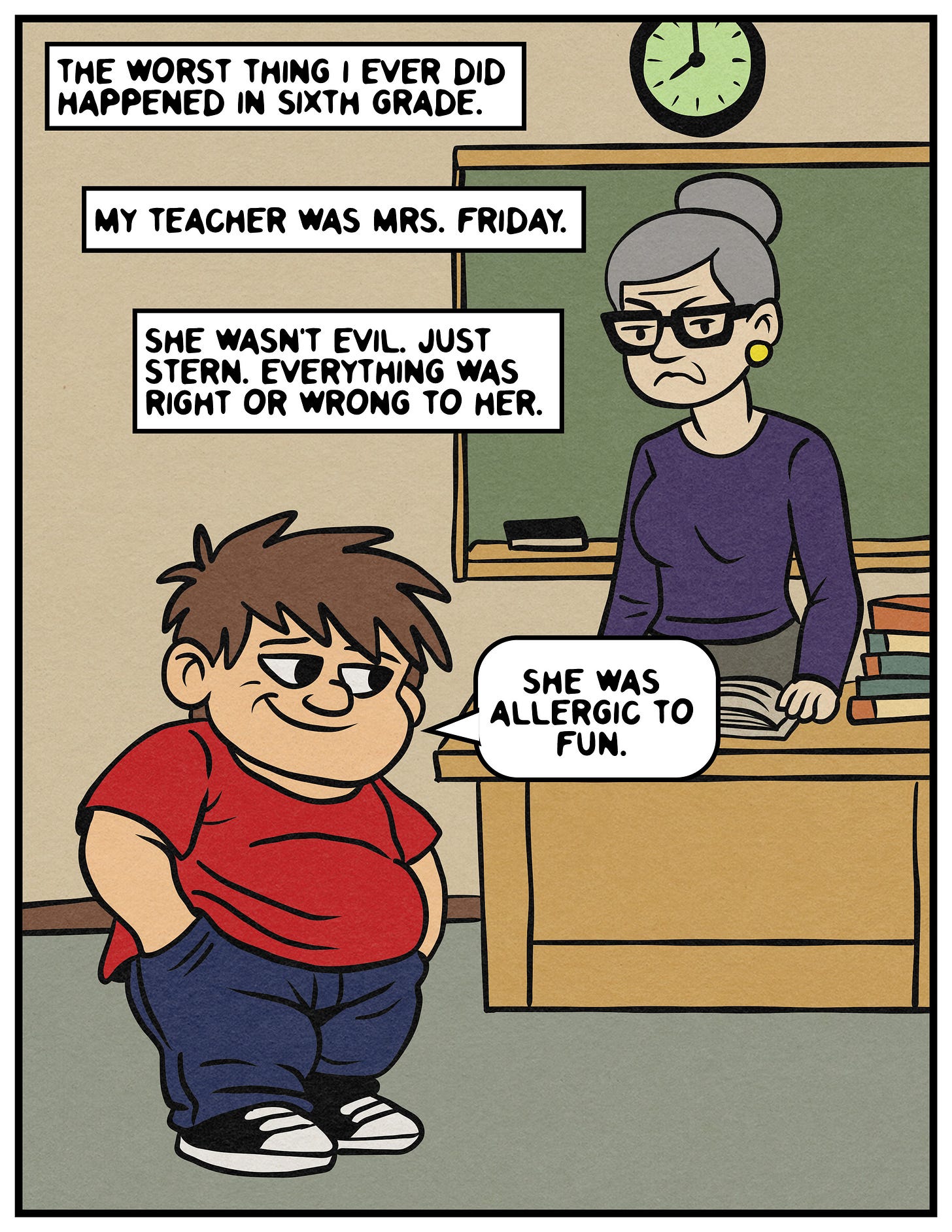

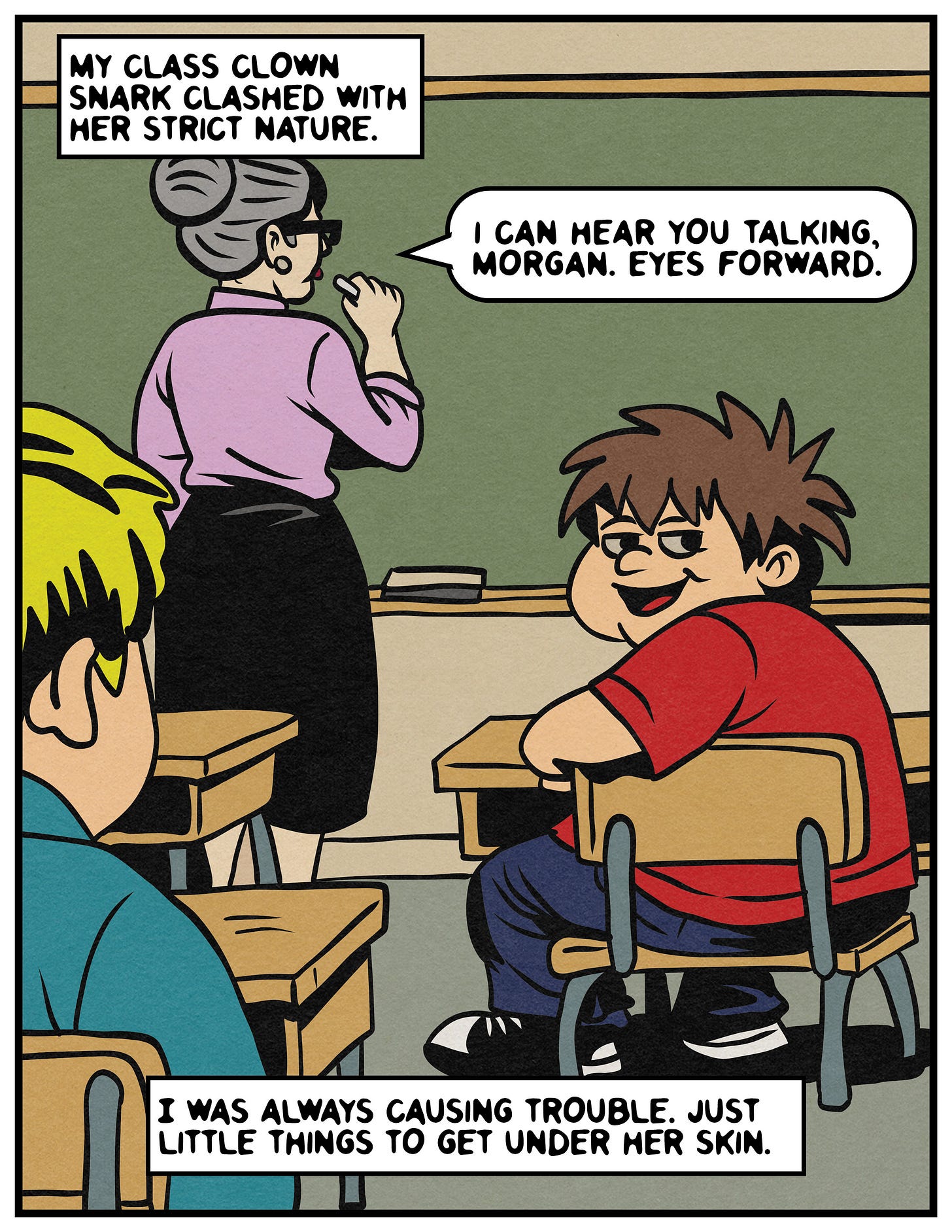

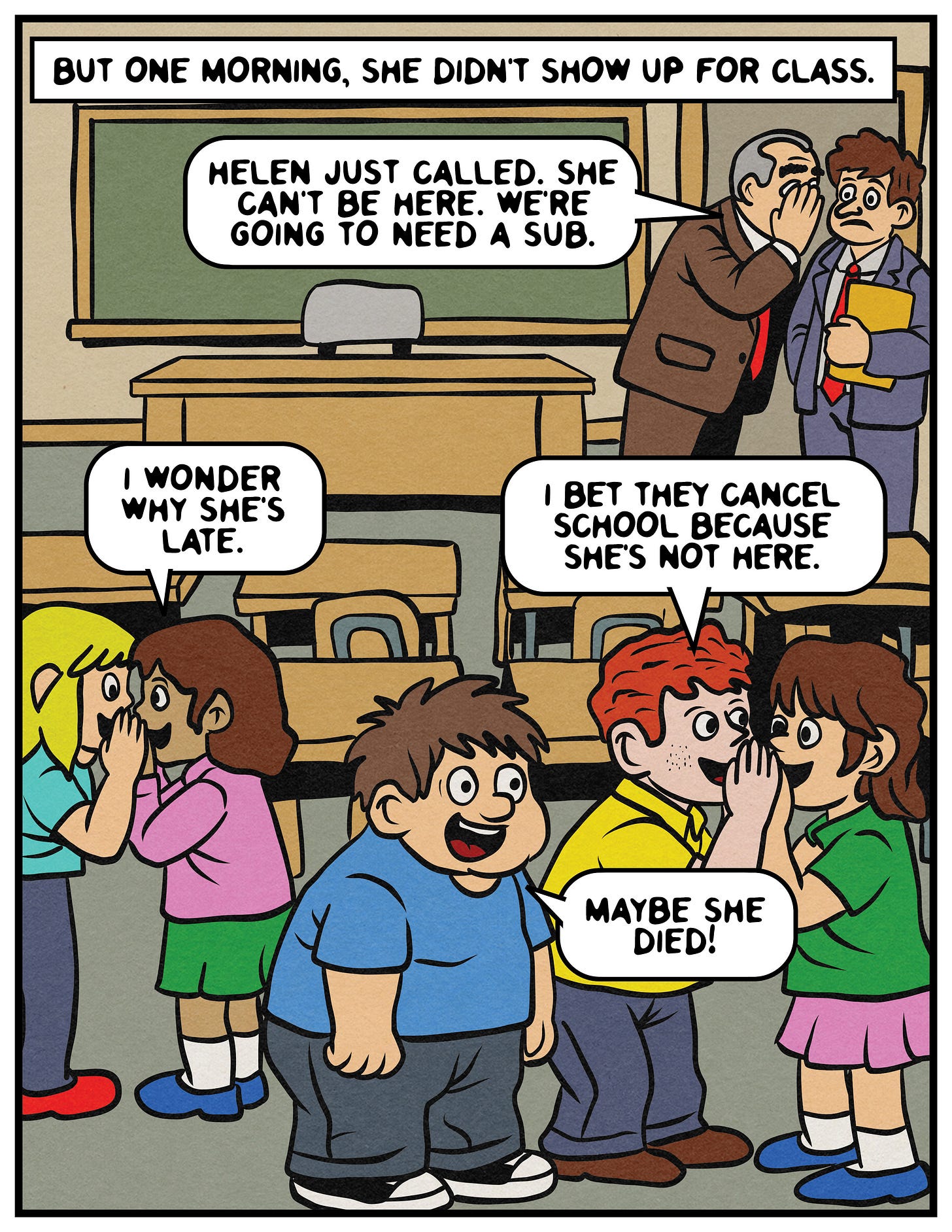

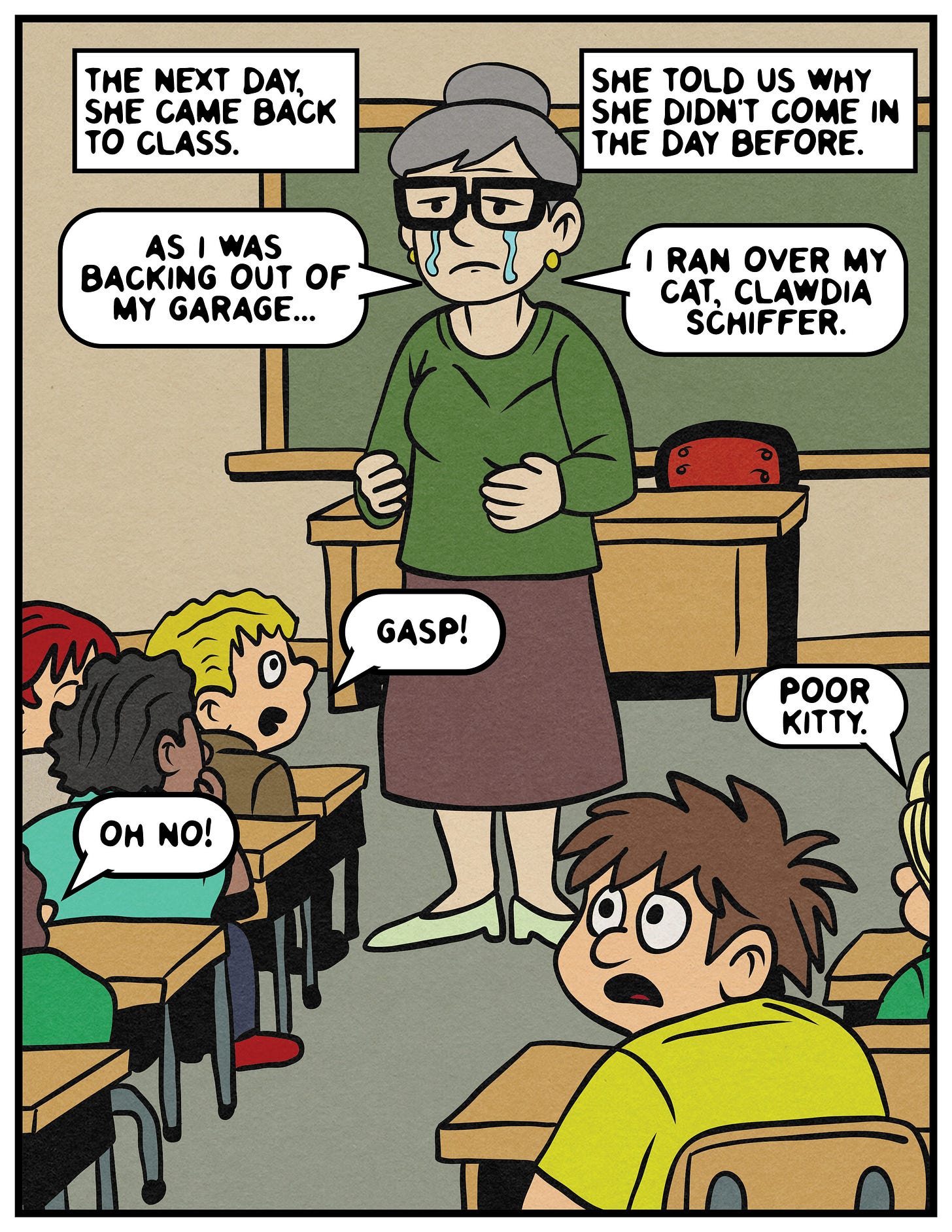

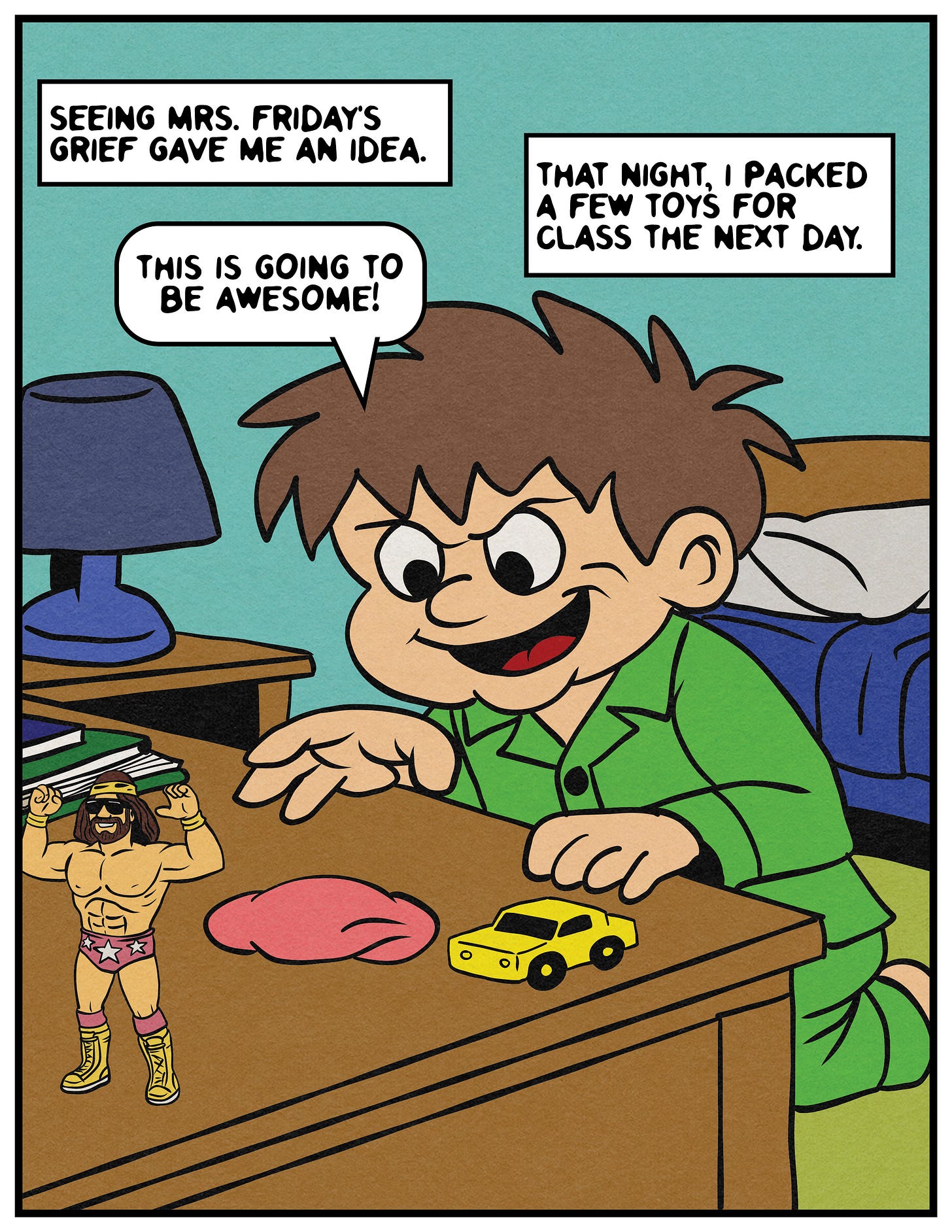

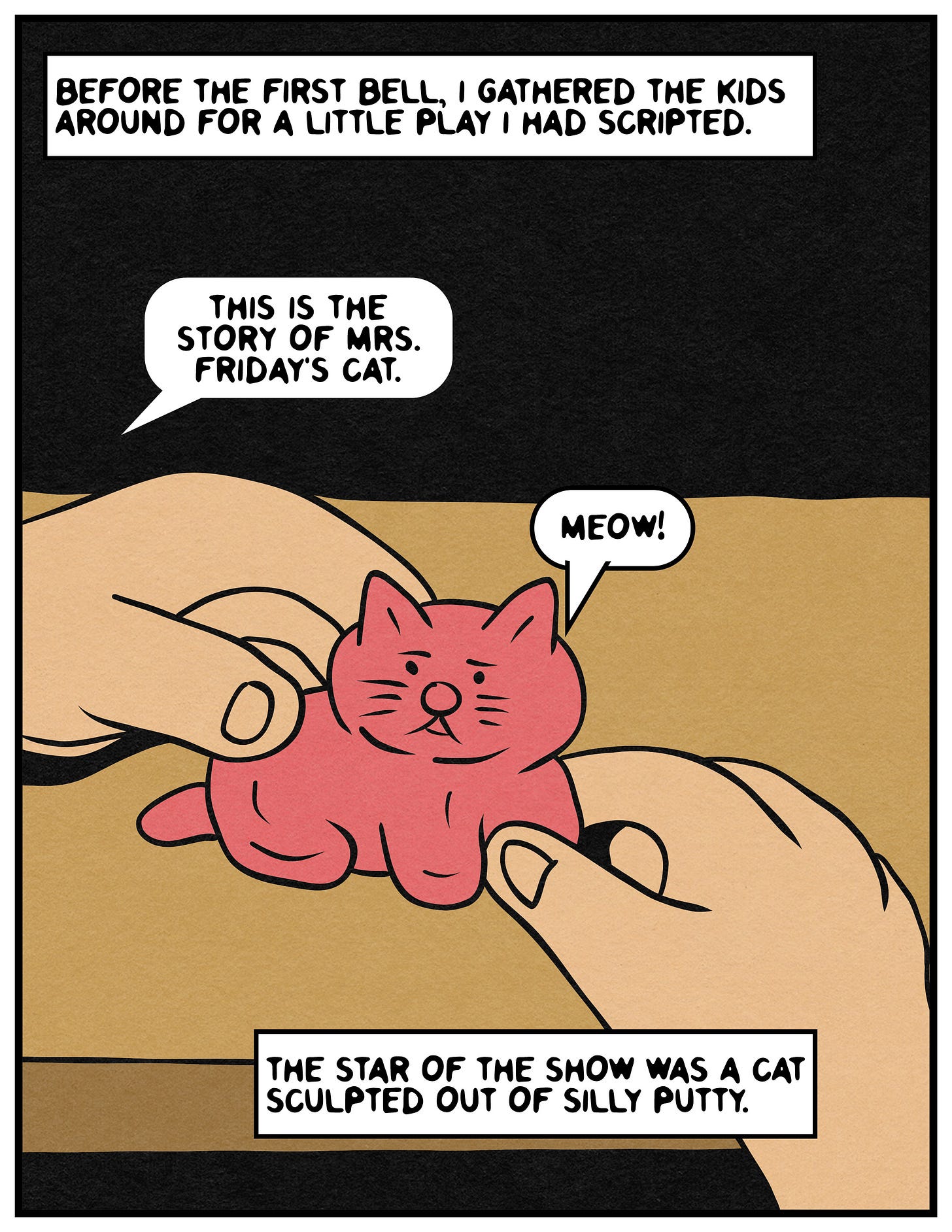

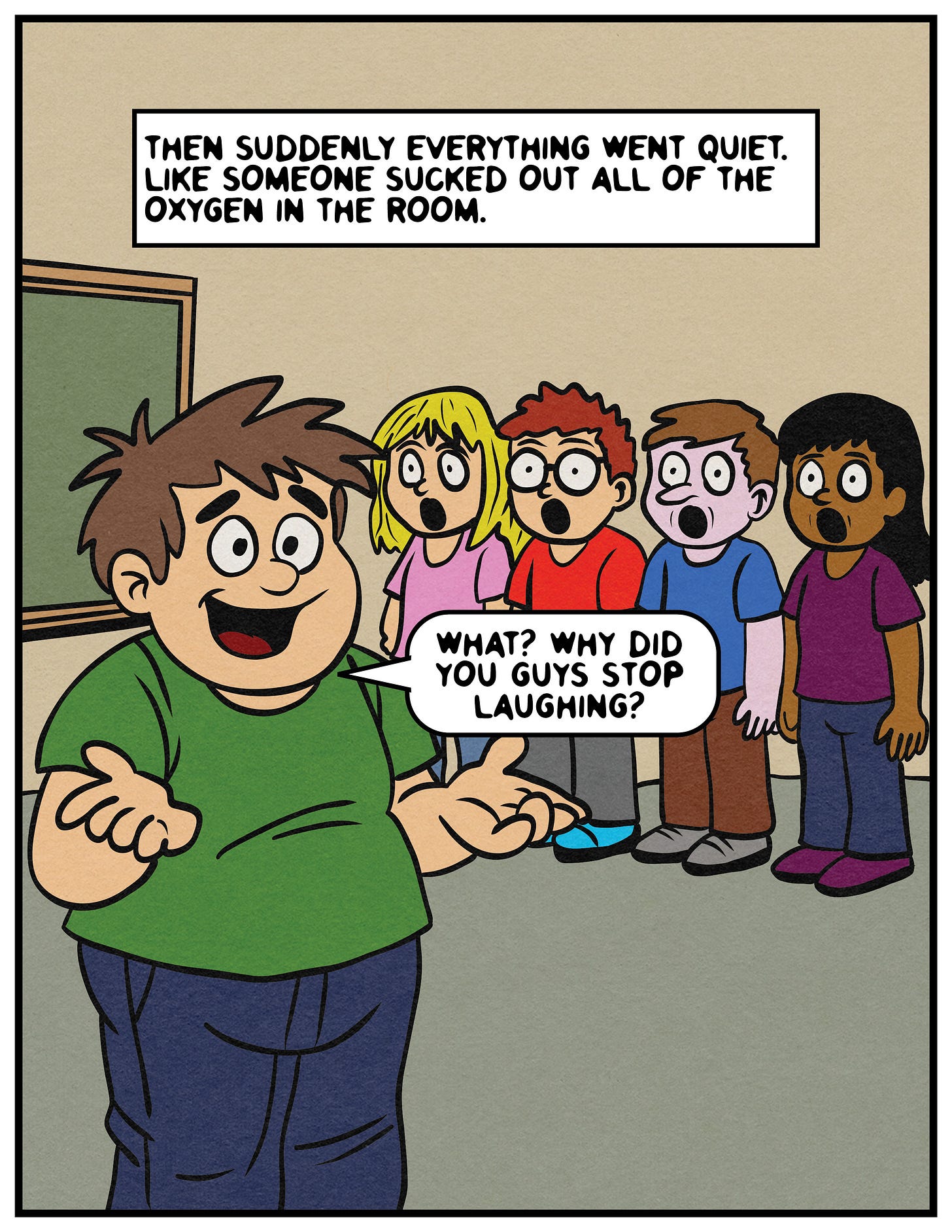

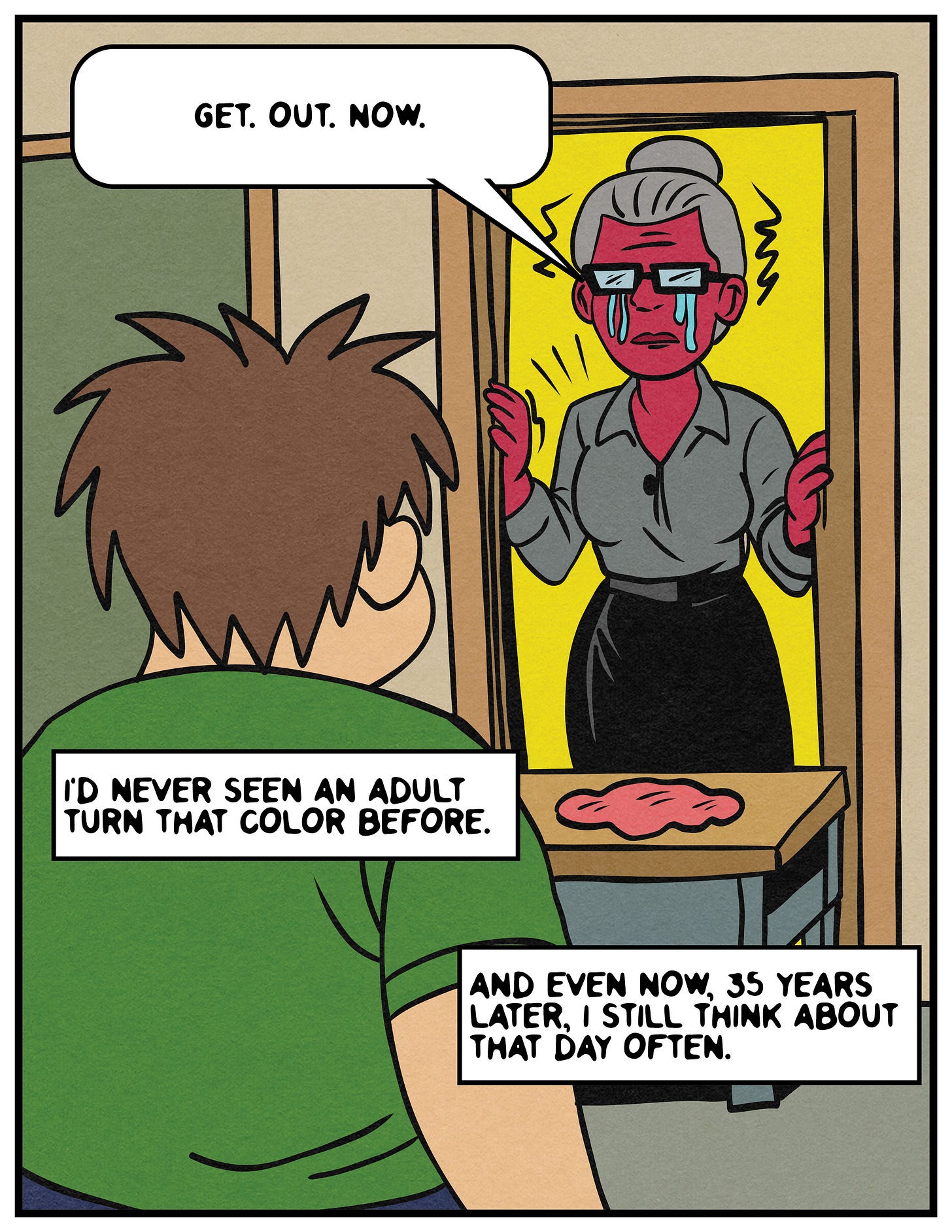

I didn’t find her like a detective. I found her like a person who hasn’t earned the right to be curious. Like I was the creepy guy peeping through a keyhole, if that keyhole involved sitting on your couch while googling retired teachers on your phone. Fifteen seconds of searching revealed her current existence, completely ignorant of the fact that I am the villain in this story. And I really do feel like the villain in this story. Heck, even now, decades later, I just used her pain as material for the comic you read before this essay.

But there she was. A name, a profile photo, a timeline full of ordinary life stuff. Evidence that the person I hurt with a stupid skit involving a Matchbox car and a Silly Putty kitty didn’t freeze like a mosquito in amber at the moment you remember last seeing them. Evidence that she kept living.

As I looked at her profile, the first feeling I felt was most definitely not noble. It wasn’t a “I want to make this right” moment. I flinched. A hot little surge of dread made me immediately swipe my Facebook app shut. Shame is a dormant seed. It can sleep for decades in the dry dirt, until a single drop of recognition creates the perfect conditions for germination.

Because now, unlike when I was eleven, there’s a new possibility: I could say something.

I could do what stories are supposed to do: write the kind of script that makes audiences nod—closure, atonement, credits roll.

Except that’s not how things usually work. An apology isn’t a receipt. It’s not proof you’ve changed. It isn’t a magic ritual that turns harm into character development.

Sometimes it can repair old wounds. But other times it’s just relief.

That’s the part I can’t stop getting stuck on. If I message her now, am I doing it for her or for me? If I’m being honest, I don’t just want to be sorry. I want to feel lighter. I want to stop hearing her name like a dropped coin in a quiet hallway. I want to stop being the villain who never got called to the stand.

That’s not remorse. That’s a deal.

There’s a difference between trying to heal and trying to launder shame. Late apologies, especially, can feel selfish. True remorse needs to be witnessed.

“Look at me, I grew. Look at me, I became the kind of person who does the right thing. Look at me, I’m brave enough to say this now.”

Even if you never write those words, the intent is there. The sender gets to perform moral progress. The recipient gets surprised in the middle of their day by a memory they didn’t ask to unbox.

That’s one of time’s sick little tricks: it makes your shame feel urgent while your victim’s experience becomes abstract. You sweat in the present; they’re just a character from your past, so your urgency feels like the priority.

But for her, the only priority may be to never think about it again.

Then again, she might remember it in a way I don’t. My wife reminds me constantly that my brain is not a video camera. It’s often a painfully unreliable witness. There’s a better than even chance that I could be the only one still obsessed with this event. I might have turned a bad ten minutes into a lifelong monster while she moved well before I entered the seventh grade. Or maybe she hasn’t. Maybe she has the high-definition cut. The sharper, crueler version, where I don’t get the benefit of the doubt, and where I can see even more awful details, my memory conveniently blurred out to let me sleep at night.

And that uncertainty—the fact that I don’t get to know—is part of the consequence.

So, again, what is an apology supposed to be for?

People talk about closure like it’s a gift you can hand someone. In reality, closure is often something the harmed person builds in your absence because you weren’t there when you should’ve been. And you showing up late can be like someone knocking down a wall in a house they no longer live in.

But both things can be true at the same time.

I genuinely want to acknowledge her humanity and stop feeling sick when I remember her face. I can want to offer respect and also want relief. I want to repair. I also want a cleaner story about myself.

Human motives are rarely pure, but that doesn’t mean inaction is the answer.

I don’t know what to do here, but I’m curious how other folks would handle this situation. So please allow me to engage-bait you into giving me advice in the comments.

And if you are Mrs. Friday (which is not really your name), and by some stroke of cosmic force you stumbled upon this comic strip recollection from a kid who was in your 1991-1992 sixth-grade class, please know that I am truly sorry. I feel horrible for what I did to you. You were so incredibly heartbroken, and you were being honest and vulnerable by sharing what happened with the class. And it was appalling how I treated you. I still think about my actions a lot. I am filled with regret and shame when I look back on how I hurt you.

I am sorry.

POSTSCRIPTUM

The other night, I told a live version of this story as part of an event my friend and I hosted in Boston. It was the first time I’d ever done long-form storytelling live—like, a couple hundred people in a room listening to me tell a story that wasn’t built to be wall-to-wall laughs.

Way back in the day, I did stand-up. And I’ve done lots of long-form storytelling in video over the years. But this was different. It was surprisingly vulnerable, and honestly? Really rewarding.

And I’m doing it again next week in Charlotte. Tickets are still available.

Also, since there are a bunch of new faces here—hi. My name is Morgan. I live on a farm in the Northeast Kingdom, and I raise cattle, goats, ducks, geese, and chickens. I’ve got a couple of livestock guardian dogs, a couple of barn cats, and hundreds and hundreds of trees.

Most people know me from the Gold Shaw Farm accounts on YouTube, TikTok, and Facebook. But a couple months ago, I started this Substack as a place to share comics and tell stories in a way that’s a little different from what I do on video—especially since I’ve gotten back into drawing. I drew constantly when I was young, then… not much in adulthood.

I post a new comic strip and essay every Monday. If you’ve been enjoying it, sharing this with someone you think would be into it would mean a lot. Word of mouth and sharing can make a massive difference when you’re just starting out.

And if you’ve got questions, drop them in the comments. I try to answer as many as I can.

I know what I’m doing here is a little weird. But I like that. The weirdness is part of what makes it fun.

Next week’s comic strip will dip back into fiction with a story about an ICE agent and a construction worker.

Hiya. New subscriber, but I worked hard to find you after seeing one of your comics. Speaking as a person who spent most of her life working with wounded and disenfranchised youth, there are few things more important to a teacher who is now (perhaps) retired, than 1) knowing that with all the hard work and good intentions and pain you experienced, you had a positive impact; 2) hearing that you’re still important even if you’re not doing the work anymore. If I were you, based on these two realities, I would approach her the way you’ve approached us: with humility and grace. I would let her know that you felt her pain as you developed empathy and that you soon understood the harm you’d caused another human and have been carrying that awareness through your life. If you _must_ bring up your shame (guilt is your conscience telling you that you were wrong and need to make amends; shame is just a lie that we are BAD for doing something wrong—it is of our own making and has nothing to do with her), you can apologise for being cruel and let her know that it helped shape you into the person you grew to be and what you’ve done with your life. Then thank her. Thank her because she is still teaching you and through you, she is still teaching others to have empathy. Hope that helps.

I believe empathy comes from love, not consequences. Or maybe both. Now that you have barn cats and have nurtured pure love for them, you are now fully realizing how distraught your teacher was over the tragic loss of her cat. Possibly a subtle nod to her by dedicating your Ginny the Barn Cat book in her honor and the greater life lesson she taught you, would be a deeper response. And then you could just send her one of the books with a personal note.

Thank you for sharing this. I think we can all think of things in our past where we have hurt someone through our words and actions, and we can all relate.